CNN

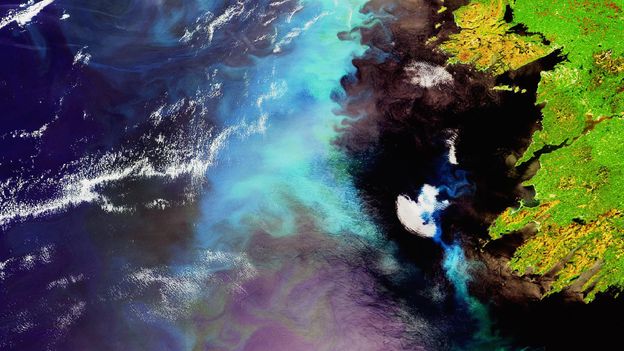

Ocean water is pushing miles beneath Antarctica’s “Doomsday Glacier,” making it more vulnerable to melting than previously thought, according to new research which used radar data from space to perform an X-ray of the crucial glacier.

As the salty, relatively warm ocean water meets the ice, it’s causing “vigorous melting” underneath the glacier and could mean global sea level rise projections are being underestimated, according to the study published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The Thwaites Glacier in West Antarctica — nicknamed the “Doomsday Glacier” because its collapse could cause catastrophic sea level rise — is the world’s widest glacier and roughly the size of Florida. It’s also Antarctica’s most vulnerable and unstable glacier, in large part because the land on which it sits slopes downward, allowing ocean waters to eat away at its ice.

Thwaites, which already contributes 4% to global sea level rise, holds enough ice to raise sea levels by more than 2 feet. But because it also acts as a natural dam to the surrounding ice in West Antarctica, scientists have estimated its complete collapse could ultimately lead to around 10 feet of sea level rise — a catastrophe for the world’s coastal communities.

Many studies have pointed to the immense vulnerabilities of Thwaites. Global warming, driven by humans burning fossil fuels, has left it hanging on “by its fingernails,” according to a 2022 study.

This latest research adds a new and alarming factor into projections of its fate.

A team of glaciologists — led by scientists from the University of California, Irvine — used high resolution satellite radar data, collected between March and June last year, to create an X-ray of the glacier. This allowed them to build a picture of changes to Thwaites’ “grounding line,” the point at which the glacier rises from the seabed and becomes a floating ice shelf. Grounding lines are vital to the stability of ice sheets, and a key point of vulnerability for Thwaites, but have been difficult to study.

“In the past, we had only sporadic data to look at this,” said Eric Rignot, professor of Earth system science at the University of California at Irvine and a co-author on the study. “In this new data set, which is daily and over several months, we have solid observations of what is going on.”